Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia App

Tranq Sleep Care developed an app to treat insomnia and published this for free use in the summer of 2022. Insomnia affects a large number of Canadians and can lead to many negative physical and psychological outcomes. Treatments tend to come in two forms: sleep medication and cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi). Since most medications are not recommended for long-term use, CBTi is the recommended long-term treatment for insomnia. CBTi involves patient education, behavioural, and cognitive components. Since there is high demand for CBTi that can’t be met by the number of sleep specialists currently available, online programs are being developed to create an effective and more accessible way to get treatment. Tranq Sleep Care developed their own program and received positive responses from a variety of users.

Medical director: Dr. Wayne Lai, MD. Program designer: Vinicio Delgado, RPSGT. Researchers: Rob Velzeboer, Renee Berger, Ted Roh. Developers: Ian Balajadia, Han Liu, Srijan Rajput. UI design: Kathleen Gonzales.

THE IMPORTANCE OF TREATING YOUR INSOMNIA

Insomnia disorder is a common sleep problem that affects almost one in four Canadians according to recent studies [1,2]. It can make it difficult to fall asleep, stay asleep, or cause early waking with an inability to fall back asleep [3]. Insomnia can cause fatigue, sleepiness during the day, reduced attention and concentration, memory problems, and impairments in motor skills. It can also lead to mental and physical health problems, such as depression, anxiety, diabetes, obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and stroke, as well as affect job performance and quality of life [4]. Untreated insomnia creates significant economic costs in North America, due to people suffering from insomnia having increased healthcare costs, reduced productivity, and decreased quality of life [5,6].

The two treatments with the most research support for insomnia are sleep medications and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) [7]. The medications currently approved for treating insomnia can have negative side effects and can create drug dependence [8-10]. CBTi is a treatment that involves patient education, behavioral modifications, and cognitive restructuring. It's considered the gold standard for insomnia treatment and is recommended as the first treatment option for insomnia [22,11]. CBTi has long-lasting benefits and doesn't have any clear negative side effects. However, CBTi is underutilized due to a lack of familiarity and training among primary care providers and limited access to sleep specialists who can administer the treatment [12,13].

As a result of this, many individuals with insomnia are unable to access CBTi [14]. To address this issue, researchers have started to develop and study online CBTi programs that can be accessed by anyone with an internet connection, regardless of location or availability of trained professionals. These programs have shown promise in improving sleep outcomes [15]. Programs often use a combination of technology and human support to increase engagement and adherence, which may further enhance the effectiveness of these interventions. As more research is conducted in this area, it is likely that online CBT programs will become increasingly available and accessible to those who need them, providing a cost-effective and evidence-based alternative to traditional in-person treatment. Tranq Sleep Care created its own 6-week program, consisting of self-evaluation, education, and self-reflection components, as well as a sleep diary and sleep restriction, and made this program freely available online. We received feedback from 18 participants.

WHAT WE FOUND

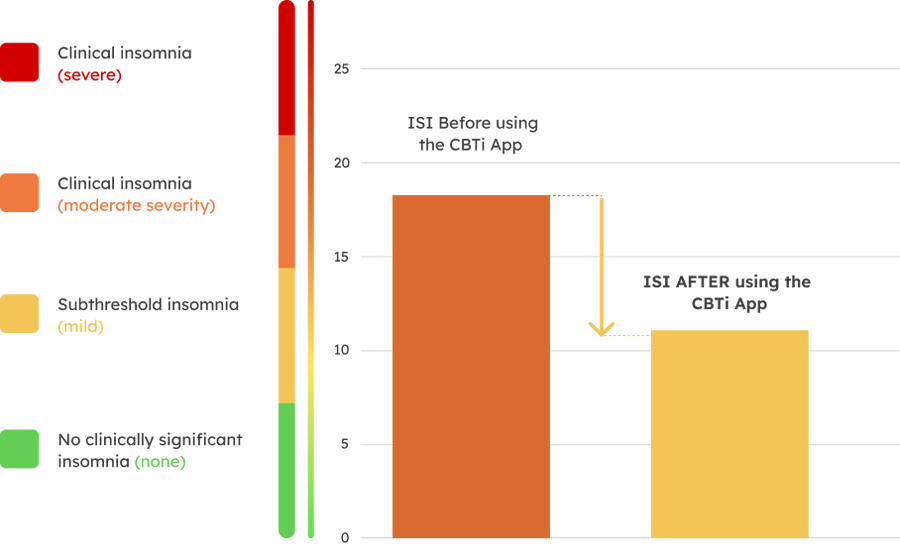

124 people downloaded our program, 18 of which gave us feedback. The participants filled out the Insomnia Severity Index before and after taking the program so that we could track how the program affected their sleep and insomnia symptoms. Insomnia Severity, which is ranked on a 0-28 scale, reduced from an average of 18.2/28 points before to 10.9/28 points after the program—a 40% reduction. This corresponds to a decrease from moderately severe clinical insomnia to subthreshold insomnia. Whereas all 18 participants had moderately severe to severe insomnia when they started the program, by the end none had severe insomnia, only 4 still had moderately severe insomnia, 9 had reduced their insomnia to subthreshold insomnia, and another 4 had reduced their symptoms to no clinically significant insomnia at all.

Insomnia Severity Index

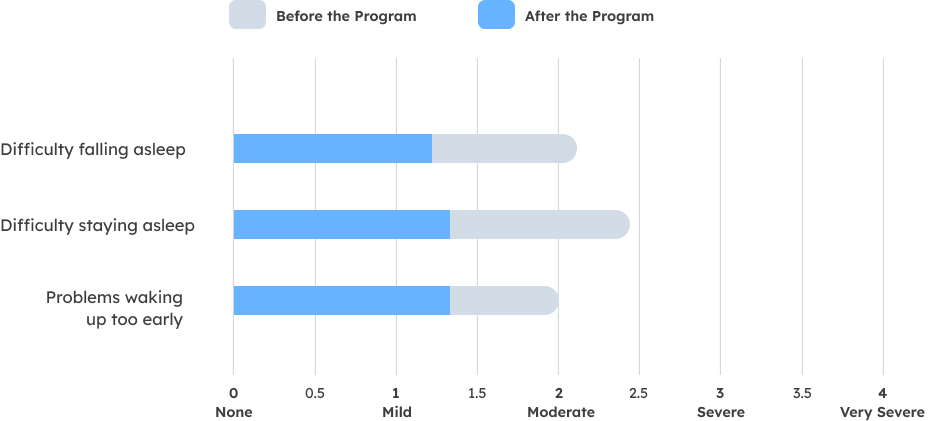

Severity of Insomnia Symptoms

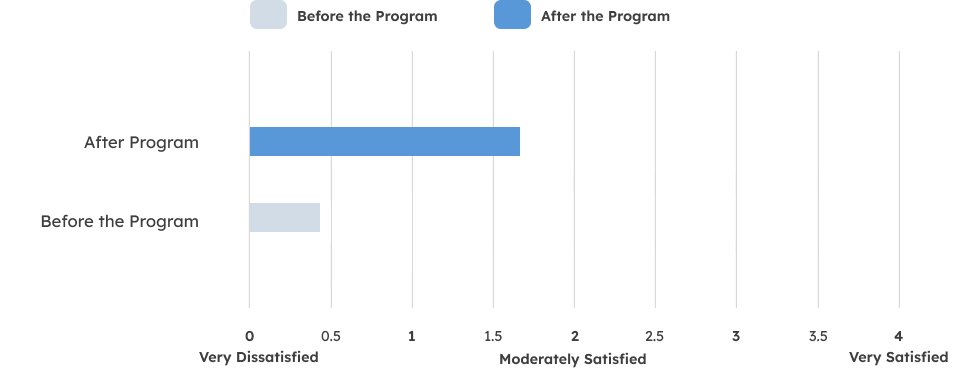

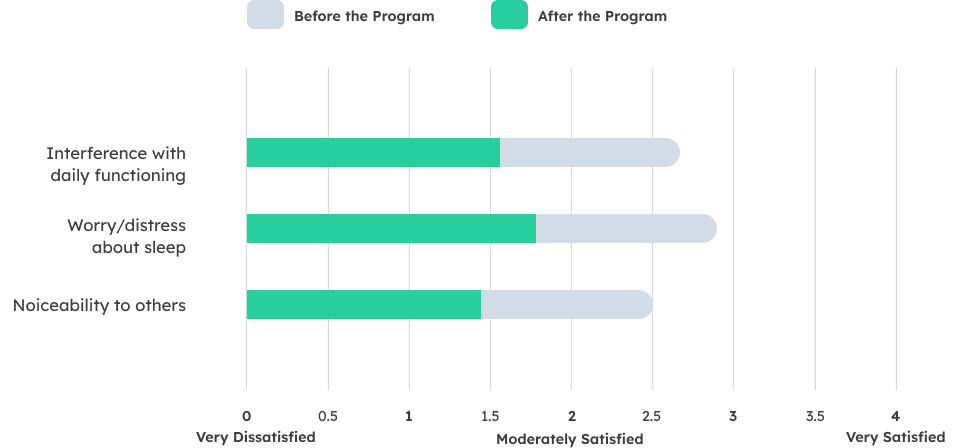

Satisfaction with Current Sleep Pattern

Factors affecting Sleep Quality

The program seemed to be more effective for participants who actively used the sleep diary and sleep restriction methods provided in the program, and was slightly more effective for patients under 40. Participants reported less severe insomnia, less difficulty falling as well as staying asleep, less worry and distress about their sleep, fewer problems waking up too early, and better functioning during the day as well as higher satisfaction with their current sleep pattern. Tranq Sleep Care is looking to keep improving the program going forward.

REFERENCES

[1] Morin, C.M., LeBlanc, M., Bélanger, L., Ivers, H., Mérette, C. and Savard, J., 2011. Prevalence of insomnia and its treatment in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(9), pp.540-548.

[2] Morin, C.M., Bjorvatn, B., Chung, F., Holzinger, B., Partinen, M., Penzel, T., Ivers, H., Wing, Y.K., Chan, N.Y., Merikanto, I. and Mota-Rolim, S., 2021. Insomnia, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international collaborative study. Sleep medicine, 87, pp.38-45.

[3] Ohayon, M.M., 2002. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep medicine reviews, 6(2), pp.97-111.

[4] Colten, H.R. and Altevogt, B.M., 2006. Extent and health consequences of chronic sleep loss and sleep disorders. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem, pp.55-135.

[5] Hillman, D.R., Murphy, A.S., Antic, R. and Pezzullo, L., 2006. The economic cost of sleep disorders. Sleep, 29(3), pp.299-305.

[6] Daley, M., Morin, C.M., LeBlanc, M., Grégoire, J.P. and Savard, J., 2009. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep, 32(1), pp.55-64.

[7] Qaseem, A., Kansagara, D., Forciea, M.A., Cooke, M., Denberg, T.D. and Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians*, 2016. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine, 165(2), pp.125-133.

[8] Voris, J., Smith, N.L., Rao, S.M., Thome, D.L. and Flowers, Q.J., 2003. Gabapentin for the treatment of ethanol withdrawal.

[9] Ramakrishnan, K., 2007. Treatment options for insomnia. South African Family Practice, 49(8), pp.34-41.

[10] Lie, J.D., Tu, K.N., Shen, D.D. and Wong, B.M., 2015. Pharmacological treatment of insomnia. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 40(11), p.759.

[11] Morin, C.M., Vallières, A., Guay, B., Ivers, H., Savard, J., Mérette, C., Bastien, C. and Baillargeon, L., 2009. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 301(19), pp.2005-2015.

[12] Cheung, J.M., Atternäs, K., Melchior, M., Marshall, N.S., Fois, R.A. and Saini, B., 2014. Primary health care practitioner perspectives on the management of insomnia: a pilot study. Australian journal of primary health, 20(1), pp.103-112.

[13] Araújo, T., Jarrin, D.C., Leanza, Y., Vallières, A. and Morin, C.M., 2017. Qualitative studies of insomnia: Current state of knowledge in the field. Sleep medicine reviews, 31, pp.58-69.

[14] Kathol, R.G. and Arnedt, J.T., 2016. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: confronting the challenges to implementation. Annals of internal medicine, 165(2), pp.149-150.

[15] Hasan, F., Tu, Y.K., Yang, C.M., Gordon, C.J., Wu, D., Lee, H.C., Yuliana, L.T., Herawati, L., Chen, T.J. and Chiu, H.Y., 2022. Comparative efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews, 61, p.101567.